One of Morton’s early pioneers observed, “The trees grow so thick, the only way to see is up.”

It was the trees — that vast sea of evergreen that stretched as far as those early pioneer eyes could see — that would one day bring growth, prosperity and fame to the little mountain town nestled in the foothills of the Cascades.

For thousands of years, the glacier-carved valley surrounded by dense forests of towering fir remained largely untouched by human hands. Only the people of the Upper Cowlitz or the occasional French-Canadian fur trapper passing through had explored this rugged land and knew the value of its pristine rivers and abundant wildlife.

That all changed when the Homestead Act of 1864 brought the first settlers to the Cascade valley with the promise of free land. Some of the earliest homesteaders hailed from Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri and other states. Others came from as far away as Norway, Switzerland and Lebanon, risking the long and dangerous Atlantic voyage. Although the land was free, it would take years of back-breaking work, determination, and grit to turn the untamed wilderness into a thriving town. Early pioneers, like Pius Cottler from Germany and the prominent Temple family, are still remembered today by the streets that bear their names.

The valley’s location at the junction of four trails made it an ideal place to settle. Although the trails were rough and took days to travel by horse or on foot, by the late 1880s, hand-hewn log cabins with puncheon floors popped up in small clearings around the valley.

Neighbors, though few and far between, helped each other survive those early years. “Rolling bees” brought pioneers together to help each other clear the land. The men would cut down trees and roll the logs into burn piles. Early settlers also participated in barn raisings, fall butchering, and livestock drives that not only accomplished necessary tasks more efficiently but brought the people together as a community. And just for fun, there were dances, picnics, and basket socials that helped break up the monotony of frontier life.

In 1884, Henry Temple brought the first cookstove into the valley. It took three pack horses and one week of arduous travel along miles of winding trails to bring the stove in from Chehalis. But how good that first loaf of freshly-baked bread must have tasted!

In 1889, the same year Washington became a state, the fledgling settlement applied for an official post office and town name. Mrs. Baumhauer had hoped the new town would be named after her because, after all, she was the first white woman in the valley. But the name of McKinley was chosen and submitted instead. However, when officials discovered that there was another town in Washington by the same name, they assigned the post office a completely different name — the name of Morton, after the current vice president, Levi P. Morton.

In 1890, George Hopgood opened the first store in the newly-minted town of Morton, selling groceries and general merchandise to the area’s homesteading families. By 1894, there were enough children in the Morton area to open a school. The first 13 students crowded into the Burnap’s tiny two-room cabin. When they outgrew that space, the school moved temporarily to the dance hall until the community built a proper log school in 1896.

The early residents of Morton were mostly subsistence farmers, raising just enough beef, bacon, butter, and eggs for their own families. They supplemented this by trapping and hunting. With little left over to sell, many industrious settlers found creative ways to make money for needed supplies.

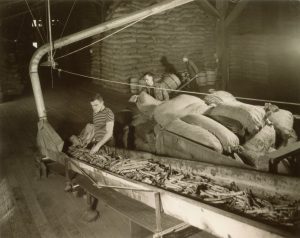

One unusual money-maker for early pioneers was peeling and selling cascara bark. At one time, Callison’s General Store in Chehalis paid 10 cents per pound for the medicinal bark which pharmaceutical companies used to make laxatives. (Lewis County residents were still cashing in on cascara bark clear until the early 1980s!)

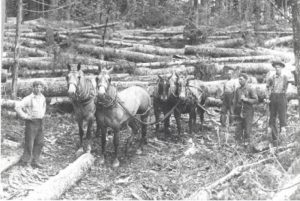

For the more adventurous, participating in stock drives from Morton and nearby Big Bottom farms to stockyards in Chehalis or Tacoma was another way men and even young boys could earn some extra cash and see the country. Considering the difficulty of transporting crops by wagon over rugged terrain, many farmers opted to raise cattle, hogs, horses, sheep or turkeys instead. These “walking crops” were popular with east county homesteaders because these were goods that could move themselves to market!

Between 1890 and 1910, shingle-bolt drives were one of the most profitable side jobs but involved the most risk. Throughout the year, western red cedar trees were felled and cut into four-foot lengths. These “bolts” were then transported to a nearby creek or river, where they were stored until early spring. When the river was high enough, crews of 10 to 15 men floated the bolts from area creeks into the Tilton River and finally into the Cowlitz River, where they made the hazardous journey to shingle mills in Kelso and Longview.

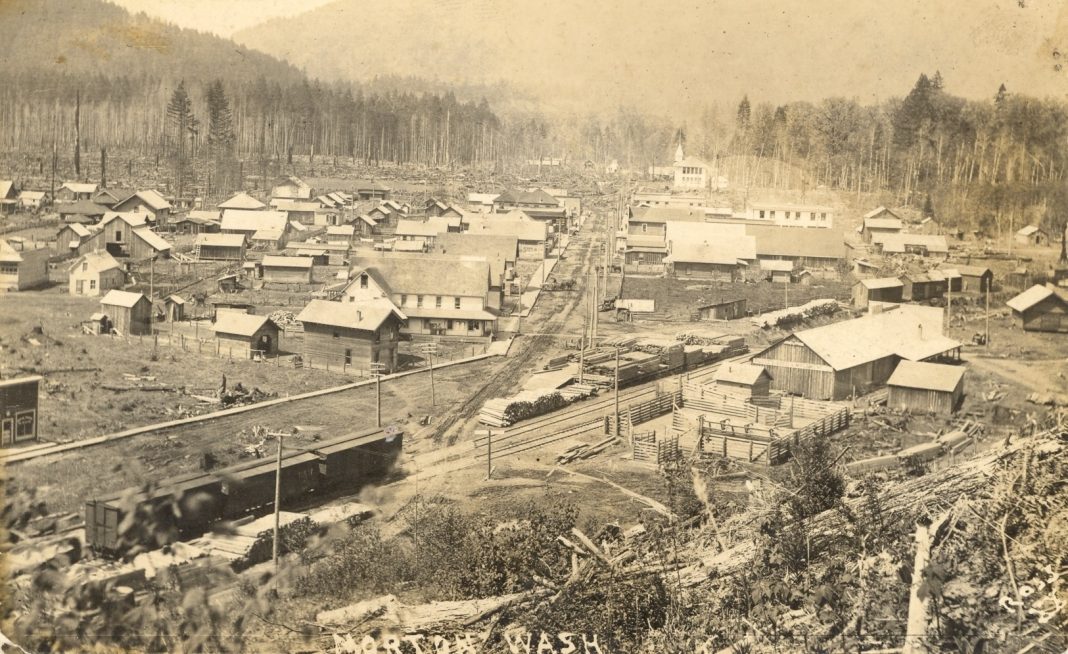

When word came that Morton would soon have a railway terminus, a few forethinking businessmen began platting the town into lots and streets. Robert Herselman and Thomas Hopgood platted the town called East Morton in 1909 near the proposed railway line, and Cottler platted an addition in 1911. Hopgood was one of the most influential businessmen in the early years and became Morton’s first mayor. These three town founders hoped their newly-platted town would draw in new businesses and residents once the train arrived. They were right.

When the Tacoma Eastern Railroad steamed into town in July of 1910, the little town’s period of isolation ended, and a new era of prosperity and growth began. With the opening of the depot in Morton, two daily trains started to run, finally providing an efficient means to transport goods to the outside world while at the same time bringing more and more people to settle. The timing could not have been more perfect.

Coal and mercury deposits found in the nearby hills soon became large-scale mining operations. Anthracite coal mines supplied coal for logging camps and locomotives and also provided heating for local homes. Rich veins of cinnabar, or mercury, discovered near Morton and surrounding areas brought in an estimated one million dollars between 1915-1930 and were believed to produce more than any other deposit in the world. It wasn’t long before Morton was known as the “Mercury Capital of the United States.”

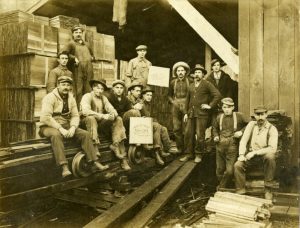

Mining wasn’t its only claim to fame. When the railroad came, large-scale logging became possible — and profitable. Almost every able-bodied man worked in the lumber industry in some capacity. If he didn’t own a sawmill, “he either worked in one, hauled lumber or ties for the local mills or logged for the timber companies,” wrote Ellen Forrest.

The first sawmill was built in 1910 and was located at the end of present-day Third Street. It wasn’t long before the timbered hillsides were being harvested, and the buzz of a hundred mills could be heard throughout the valley. Over 80 mills cut nothing but railroad ties, soon earning Morton another nickname, “Tie Mill Capital of the World.” Set up on the tops of surrounding hills, these portable tie mills turned timber into railroad ties that were then transported down the mountains to the railroad. This once-obscure town now boasted the largest and longest tie dock in the world!

During the late 1930s to early 1950s, the height of the tie boom, railroad ties from Morton were transported worldwide. The mills used second-growth Douglas fir trees which were the ideal size for ties. Old growth trees were too large for the mills to handle. During World War II, ties from Morton were used to build the Burma Road. Following the war, a large number were shipped to Europe to help repair the hundreds of miles of damaged rail lines.

The railway also brought several enterprising businessmen to the growing town who helped develop the Morton commercial district. Charles Winsberg, originally from Michigan, opened a farmer’s exchange where he sold dry goods, hardware, feed, grain, and livestock. He also built the first house in Morton with an indoor toilet and bath. Other businessmen, like Fairhart, Childers and Phelps, made their mark on the town. Fairhart built a store and hotel, Childers sold hardware, and Phelps opened a clothing store. In 1911, the first bank, the State Bank of Morton, was chartered and opened.

With a railroad, post office, school, hotel, bank, growing business district and thriving timber and mining industries, Morton was no longer just a little village. It had become an important trading and social center — with a growing need for law and order. While bringing profit to the area, the lumber industry also brought the social challenges that arose when crowds of young, hard-drinking, hot-tempered loggers descended on the town.

Concerned citizens who desired a safer environment for raising children and “one that would protect the property and opportunities for business ventures” pushed the idea of incorporation. So, on January 6, 1913, a petition with the signatures of 60 pioneers — including 16 prominent women known as the founding mothers of Morton — was submitted to the Lewis County commissioners requesting incorporation. The commissioners signed the document “which would give local authority to bring law and order to a booming frontier town in the Cascade Mountains of Lewis County,” recalled Woodrow Clevinger.

Over the years, the logging town would face Spanish influenza, a devastating fire in 1924 that destroyed over 60 percent of its business district, the Great Depression, flooding, two world wars, and economic challenges. Despite the hardships, Morton continues to persevere with grit and determination — just like its pioneer founders.

Today, Morton’s idyllic location on the White Pass Scenic Byway at the crossroads of Highway 12 and State Route 7 makes it the perfect stopping point for adventurers wishing to explore Mount Rainier or Gifford Pinchot National Forest. Tiny coffee shops, a live theater, the renovated Historic Depot and Visitor Center and the annual Morton Logger’s Jubilee, a celebration of the town’s proud logging roots, draw both locals and visitors to the little mountain town nestled in the foothills of the Cascades — a place where folks can “breathe easy in the mountains.”