The story of Packwood begins at the eastern edge of Lewis County, where the snow-capped peaks of the Tatoosh Range rise to touch the sky, a land where pristine mountain lakes sparkle like hidden gems and glacier-fed streams descend through the towering evergreen forest into the Cowlitz River below.

For hundreds of years, this rugged, untamed wilderness in the shadow of Mount Rainier was home to the peaceful Upper Cowlitz people or Taidnapam. They made their summer camps on the banks of the Muddy Fork, Skate Creek, and Hall Creek, where the glacial waters flowed into the Cowlitz River. Here, the people gathered huckleberries, fished in the abundant mountain streams, and hunted wild game, which they dried and preserved for winter. Year after year, the land provided all that they needed.

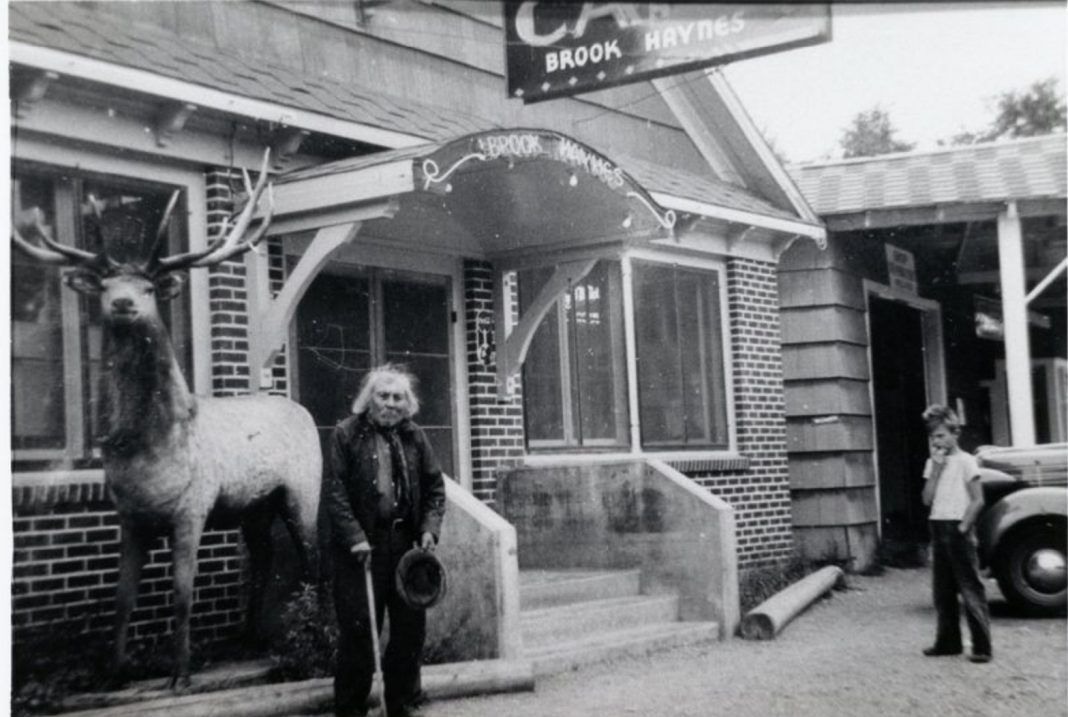

Citation: Jim Yoke, Ohanapecosh Discoverer’s, 1890-1910, State Library Photograph Collection, 1851-1990, Washington State Archives, Digital Archives, http://www.digitalarchives.wa.gov, accessed 12/29/2021

During the summer of 1854, their lives would forever be changed.

One day, two white strangers approached their summer camp accompanied by three Nisqually men. The explorers had come from distant Tumwater searching for a better pass through the Cascade Mountains. The small expedition had traveled up the Nisqually River, skirting the base of Mount Rainier through Bear Prairie and finally down Skate Creek.

A young Cowlitz boy, later known as Jim Yoke or “Indian Jim,” was fishing along Skate Creek when the strangers came. He recalled how startled he was to see two men with pale, hairy faces. This was the first time he had ever seen a white man, and he was terrified. “Me lun-um, me lose pish” (I ran, and I lost the fish), Yoke admitted years later.

The white strangers who caused young Jim to lose his fish were early Oregon Trail pioneers James Longmire and William Packwood. Thinking they had found the pass, they were disappointed to later learn that the Cascades were still several miles to the east!

However, their exploratory journey down Skate Creek was not in vain. Although Packwood and Longmire did not find the mountain pass on this journey, they discovered a thriving and friendly Cowlitz village hundreds strong and a long river valley rich in natural resources and rugged beauty. This remote land of the Upper Cowlitz later came to be known as Big Bottom Country and was one of Lewis County’s last frontiers.

While he never settled in the area, Packwood returned several times to the upper Big Bottom exploring and prospecting. He discovered the picturesque lake that bears his name and eventually located Cowlitz Pass (near present-day White Pass), finally achieving his goal of connecting the eastern and western sides of the Cascades. In 1869, Packwood also discovered high-quality anthracite coal near Coal and Lake Creeks. He put in a claim and returned yearly to work his mine. However, it would be many more years down the road, and a few name changes later before the little town at the foot of the Cascades would claim Packwood’s name for their own.

Because of the remoteness of the territory and extreme difficulty in reaching it, American settlers did not begin arriving until 1883, nearly 30 years after Packwood first stepped into the valley. After learning of the Northern Pacific Railroad survey up through White Pass in 1880, some may have been drawn to the area with the hopes that a railroad would soon be following. However, the railroad never came, and the region remained isolated for many more years.

One of the first homesteaders in the area was Levi A. Davis and his family, the same family who founded the once-promising town of Claquato. After his attempt to secure Claquato as the county seat failed, Davis moved his family further east in 1883 in hopes of starting anew. Davis and his three sons homesteaded a few miles west of present-day Packwood. They and the settlers that soon followed–the Blankenships, Snyders, Halls, Owens, Sethes and Combs — all faced enormous challenges as they worked to tame the wilderness.

There were no easy trails from Chehalis to the upper Cowlitz River valley in those days. Early settlers packed everything in on their backs and made the dangerous 75-mile journey by foot, following old Indian paths or blazing their own trails through the dense, uncharted wilderness where cougars, bears and wolves roamed. Men usually went ahead, filing a claim and building a cabin before bringing back their families.

Later, pack and saddle horses were used to carry supplies from Chehalis to the isolated homesteads. Even when the trail was widened enough to allow wagons, the tedious journey still took one week, and that was when the river was low enough to ford. If the Cowlitz was high, settlers had to unload all their supplies, dismantle their wagon, ferry everything across in dugout canoes, swim their horses across, reassemble their wagon, and load it back up before continuing. Imagine their excitement and relief when the first ferry boat started operating in 1905!

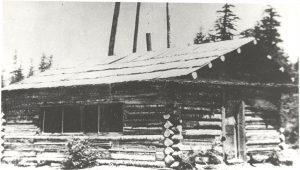

Clearing land was another enormous hurdle. Some claims were so heavy with timber that it took farmers several backbreaking years to clear their land for crops and pasture. Many had to work at other occupations in order to get by until their land could sustain their families. Before lumber mills were up and running, homes and furniture were all painstakingly built by hand. Most early homes were constructed of logs or split cedar with puncheon floors. With neighbors few and far away, life was hard and lonely.

Their one connection to the outside world was through the mail. In 1890, the first post office in the upper Big Bottom was established at the Davis homestead and named Cora after a favorite niece. It was not long before another post office opened at Sulphur Springs, closer to where present-day Packwood is located. In the beginning, men in the remote settlements each took turns delivering mail by horseback riding the six-day circuit from Sulphur Springs to Randle and back. Settlers hung a small canvas or oilcloth sack on a post near the road. The mail carrier picked up the sacks, hung them from the saddle horn, and delivered them to the post office. New mail was placed back in the respective bags and delivered on the return trip.

As more people came to the east end of the county, schools were built to meet the educational needs of the children. The first school was built around 1908 on land donated by the Combs family. Everyone pitched in. From donating lumber to providing labor, the local residents worked together to construct the 16 x 20-foot log building with a hand-split board floor and homemade wooden desks and seats. Boys sat on one side, girls on the other. How proud those first 11 students must have been of their brand-new log cabin schoolhouse!

In 1910, August Snyder and Hugo Kuhnhausen hired a surveyor to plat a new town near the Sulphur Springs settlement. The post office was moved there from Sulphur Springs and renamed Lewis after the president of the Valley Development Company. Kuhnhausen moved his store to the townsite, and Walter Combs built the first hotel. Roads had improved enough to deliver mail by “hack” or spring wagon. And thanks to the construction of the first sawmill, which provided good lumber at a cheap price, the fledgling town of Lewis started to take off.

As more homes began to spring up around town, other businesses soon followed. Freight and stage lines started to run. A slaughter business provided meat to the community and the busy construction camps. Local farmers who now had a ready market for their hay and produce also organized the first telephone company in the region. Practically every family along the road owned a phone and could now call outside the valley. It was the beginning of a “good little town.”

Although their daily life was filled with hard work, the settlers took time off to have fun and socialize. The log cabin school became the natural gathering place for community events, including the first social club called the “Lewis Debating Club” and later dubbed “The Ohanapecosh Literary Society.” Social activities, debates, programs, and socials were all held at the schoolhouse until a separate community hall was built in 1912.

The new community hall was more than double the size and boasted a dance floor, cloakroom, two dressing rooms, and a large stage. Entire families came by horseback and wagon to dance the night away. Local musicians provided the fiddle and piano music, and the ladies provided a “midnight lunch.” When the little ones tired out, they were put to bed on the stage while the grown-ups danced until daylight.

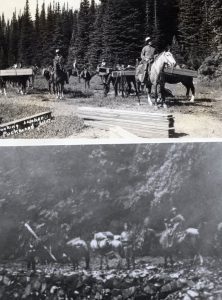

Situated so close to the natural beauty of Mount Rainier and the Cascades, Lewis soon became an important base for the US Forest Service as well as a recreational hub for tourists visiting the national park or forests. As the Forest Service work expanded in the early 1920s, there was more demand for pack horses and saddle horses to supply those working on the forest trails, telephone lines, and at fire lookouts. Local outfitters also took advantage of the region’s growing popularity as a tourist destination. Several pack and saddle companies offered visitors guided horseback trips to the relaxing hot springs near Mount Rainier or to the high country to fish in crystal blue lakes teeming with trout.

In 1929, the White Pass Highway was completed to Lewis, a “milestone” achievement that made it possible for automobiles to now drive all the way to the town at the end of the road. Around this time, the town’s name of Lewis started causing confusion for the U.S. Post Office. Mail was frequently mixed up between Lewis, Fort Lewis and Lewis County. In 1930, to clear up the confusion, the town decided to change its name to Packwood to honor the first pioneer trailblazer who set foot on the land where their town now stood.

Fittingly named for an adventurer and explorer, the town of Packwood continues to welcome those who seek adventure. From fishing and hiking in the summer to skiing and snowboarding in the winter, Packwood is the perfect destination for those wishing to explore the same rugged splendor that drew early settlers and visitors to the wild, untamed beauty of the upper Cowlitz Valley.

Historical Notes

Researching the history of Packwood uncovered more fascinating facts than would fit into this article. Here are just a few of them:

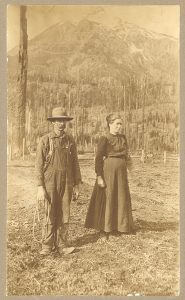

The Upper Cowlitz or Taidnapam people lived in the upper Big Bottom Country between present-day Mossyrock and Packwood. A few well-known Taidnapam figures include Cowlitz patriarch Jim Yoke, also known as “Indian Jim,” who homesteaded in the area with his Yakama wife Annie and became an integral part of the Packwood community, participating in community events and voting in the first election. Baptiste “Bat” Kiona, a friend and neighbor to the Davis family, was hired by the county to run the first ferry across the upper Cowlitz for a salary of $30/month. One of Lewis County’s oldest residents was Cowlitz woman Mary Kiona, who some say lived to be 115 to 120 years old! She was greatly admired for her skilled basket weaving.

When traveling by foot, early settlers carried their personal belongings in cloth flour sacks nicknamed “Big Bottom Suitcases.”

Two of the early settlers were German brothers William and Joe VonOy. One day, while they were driving their wagon back from Chehalis, one of their horses died. William, the smaller and bossier of the brothers, hitched his younger brother Joe to the remaining horse Mike. A settler who was watching the strange pair pull the wagon as they passed by saw the strapping young man in the harness poke the horse and shout, “Come on, Mike, do your part!” Joe “helped” plow the fields the following spring in the same manner. Such were the tales told of those rugged pioneers!

In the spring of 1914, more public land was opened for homesteading, and an official “Land Rush” was declared for May 1. Those interested in claiming free government land had to begin at private property and be observed by two witnesses. At 8 a.m. sharp, competitors had to “make a run for the piece of land desired. The first one to reach the property and stake it was the ‘lucky one.’”

In the early 1930s, the Great Depression brought young men from all over the country to Packwood and the surrounding areas to work for the Civilian Conservation Corps or the CCC. Many were based at the permanent camp in Packwood and smaller camps nearby. They worked on building new trails, roads, telephone lines, and buildings and repairing old ones. They constructed the La Wis Wis camp and picnic area, the Ohanapecosh campsite, the Packwood cable bridge across the Cowlitz, four fire lookout stations, three guard stations and several other buildings. They served as fire lookouts and forest firefighters. The young men of the CCC made a lasting impression, and their works are still admired in the national forests and parks surrounding Packwood today.

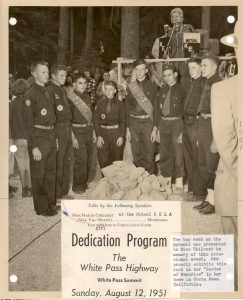

World War II brought a growing demand for old-growth timber. Soon hundreds of miles of new logging roads crisscrossed the high country, and millions of feet of timber were harvested from the old-growth forests above Packwood for use by the U.S. Army. After the war, the timber industry remained an essential part of Packwood’s economy and included several lumber and shingle mills. Highway construction over the pass, which had been halted during the war, resumed. White Pass Highway was finally completed in 1951.