The COVID-19 pandemic is not the first time a national health crisis shut down local schools. Just over 100 years ago, schools in Lewis County were forced to close their doors more than once while the “Spanish Flu” swept through Southwest Washington. Surprisingly, the 1918 influenza pandemic led to many of the same challenges that schools and families face today.

Lewis County Schools Close

In the fall of 1918, just as World War I came to a close, the worldwide epidemic that had been wreaking havoc across the globe finally reached rural Lewis County forcing most schools in the area to shut down by early October. The closures, issued by the state board of health and recommended by both city and county health officers, upset the familiar rhythm of life for students, teachers and parents.

Many area schools closed the second week in October when the first 40 cases appeared in Chehalis.

“New Disease Hits This City” rang the headline of The Chehalis Bee-Nugget on October 11, 1918. “The Spanish Influenza, which is spreading all over the country, hit Chehalis this week, and as a result, the local schools, theaters and all public gatherings have been closed until the malady is conquered.”

Chehalis, Adna, Bunker, and Centralia schools all closed that week. “Owing to Spanish influenza, the local schools were closed yesterday. A patriotic meeting that was to have been held Friday evening (in Adna) has been called off,” reported The Nugget.

One week later, The Centralia Daily Chronicle ran a similar alarming headline: “Influenza Epidemic Causes Many Deaths.” The article opened with foreboding news. “Chehalis has been hard hit by the Spanish influenza epidemic…” There were now eight deaths and 60 reported cases. “No public gatherings of any kind have been allowed, and the places in Chehalis where people are wont to congregate, even in small numbers, have been shut down tight all week, and will continue to be closed until the health officials deem it safe to reopen them.”

Teachers and the State Training School Also Affected

Students were not the only ones impacted. The annual Lewis County teacher institute and the scheduled teachers’ examinations in early November had to be canceled. Many teachers remained in the area waiting indefinitely for schools to reopen. Thankfully, “teachers in all public schools of the state (received) their salaries during the forced vacation caused by Spanish influenza,” reported The Chronicle on October 24.

The influenza epidemic touched all students, including those incarcerated at the state training school in Chehalis (known today as Green Hill). In early November, local health officials placed the training school under quarantine “on account of the influenza, and no mail matter is allowed to leave the school and no packages allowed to be received nor visitors permitted on the grounds,” reported The Chronicle.

Mask-Wearing Recommended

On November 1, the State Health Board recommended the wearing of masks in public—in spite of the reprieve in the number of cases. “There are not quite so many cases reported in Chehalis and vicinity, and they are said to be less dangerous. However, there are a large number of cases here yet, and the public is warned to be on its guard and use protective measures strictly,” reported The Nugget.

As if influenza cases were not enough, Lewis County school districts also had to deal with a number of smallpox and diphtheria cases at the same time, sparking some controversy over the legality of requiring vaccinations and quarantines for school children. “Nearly every family is having the children vaccinated for smallpox, although the school board says it has not the (legal) right to enforce this,” reported The Nugget.

Ban Lifted and Schools Reopen

Over the next few weeks, the number of flu cases decreased. When there had been no new cases reported for four consecutive days, the influenza ban in Chehalis was lifted. On November 12, schools and theaters could open again, and public gatherings were allowed. Due to “so much time having been already lost,” Chehalis schools reopened the first day after the ban was lifted, according to The Nugget. However, plans were still being discussed at the state level as to adjusting the school calendar to make up for lost time.

Advocates for reopening area schools reassured the public that safety measures would be taken first: “To relieve their minds we will state that fumigation will remove the danger. Children living in homes where influenza exists will not be permitted to enter school,” reported The Chronicle.

Toledo reopened on Thursday, November 14, and Adna reopened the following Monday.

Morton Schools resumed class on November 18, “and there was joy unconfined when normal conditions were restored,” reported The Chronicle. All the school buildings were thoroughly fumigated prior to students returning.

Cases Increase and Chehalis Schools Close Again

However, the move in Chehalis turned out to be premature. Shortly after the ban was lifted, City Health Officer Kennicott ordered the closure of Chehalis schools once again. “They had just been in session one week after lifting the influenza ban, and it was soon discovered that many new cases of the epidemic were being reported, apparently following the re-convening of school. It was decided best to close them down again to avoid a greater spread,” reported The Nugget on November 29.

Although the new cases in Chehalis did not appear to be as serious as the first ones, it was predicted that Chehalis schools would not likely open again until after the first of the year.

When the ban was lifted in mid-November in the west county, Superintendent Canterbury wrote to school directors permitting Boistfort-area schools to open, but added, “If you feel that there is danger in starting now, postpone until you think it safe,” recorded Pricilla Tiller in her book, The Wooden Bench. The directors responded by opening schools in outlying wards “where there (was) no sickness, such as Wildwood, Halfway and Lost Valley,” but they delayed opening other schools until there was less sickness.

Curtis School reopened in early December. Lake Creek waited until December 16.

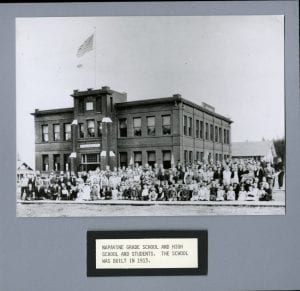

New Boistfort High School Finally Opens Doors

On December 9, Pe Ell schools reopened, and on the same day, the long-awaited grand opening of Boistfort’s new high school finally took place. “Golden-colored Boistfort High School, pride of the valley, opened December 9, 1918, as Spanish Flu subsided,” wrote Tiller.

The new Boistfort High School building had been scheduled to be completed in the early fall, and students had eagerly anticipated its opening: “Every day, high school boys and girls wander through…to see by some miracle if it hasn’t been finished in the night,” wrote Tiller. The excitement of moving into their new building that fall was quenched by the “invasion of the fearsome Spanish Flu” that delayed opening day nearly two months.

School Board Fights to Reopen Chehalis Schools

Around the same time as rural schools were reopening, Chehalis Schools remained closed—a topic of heated debate in city commission meetings. During one meeting in early December, A.S. Cory, a local school board representative pointed out “that children were attending shows” and that “if the children could go to the shows–they could go to school.” Cory advocated for opening the schools as soon as possible: “If the children can still mingle in crowds, there is nothing gained in closing down the schools,” reported The Nugget on December 6.

The same issue was rehashed a week later. “The school board objected to the schools being closed while children were allowed to attend shows, Sunday school, and other places where they might congregate.” Cory pointed out that even doctors did not seem to agree about the disease and quarantine regulations and closing things did not seem to get the desired results.

According to The Chronicle, that meeting resulted in a ruling that banned anyone under 21 from movies and included strict enforcement of the smallpox quarantine. It did not, however, lift the ban on Chehalis schools.

At a city commission meeting in late December, Chehalis Superintendent Cook spoke on behalf of the schools, blaming the district’s great financial loss on the closure. He suggested schools could “put in a nurse and send home any child having the influenza,” reported The Nugget on December 20.

Despite the pressure, Chehalis schools remained closed for almost two more weeks. The second ban was finally lifted at the end of December and school resumed on Monday, December 30. “…it is not thought it will be necessary to interrupt the school program again. As large an attendance as possible is desired when the schools open,” The Nugget reported.

Learning from Home is Not a New Thing

Unfortunately, the new year did not bring an end to the influenza epidemic nor its impact on education in the county. In early January 1919, several families in the Mossyrock area were infected with the virus. “The Mossyrock schools are all running, but the attendance is rather light,” reported The Nugget.

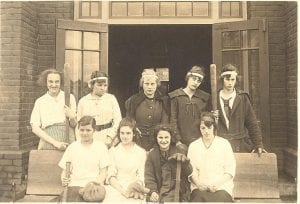

In Napavine, attendance also declined with the new year. At one point, half of the high school was absent. Following the recommendation of the county health officer, Napavine schools closed again in mid-January.

Interestingly, the students themselves requested an opportunity to learn from home to continue their studies. “Many of the pupils expressed a desire to do homework under special supervision of their respective teachers.” With permission from Superintendent Bright, the teachers arranged “with such pupils to take assignments as they left school and to bring those assignments at a date set by each teacher, at the teacher’s home, at which time other assignments (were) made,” The Nugget reported on January 17.

A Lesson from History

An epic epidemic, county-wide school closures, disappointed students, frustrated school boards, case numbers rising and falling, quarantines, mask requirements, disinfecting schools, and learning from home–these are not as “unprecedented” as we might think.

Just over one hundred years ago, the generation that helped win World War I also battled the same kinds of health dangers, school closures, frustrations and challenges that we face today in a similar pandemic.

Historical records reveal that after a long, hard battle that generation survived the influenza and moved on. In Lewis County as elsewhere, the flu eventually died out. Schools and businesses reopened and stayed open, and the painful disruption the epidemic caused was all but forgotten in the dusty annals of history.

If our forefathers could overcome such a devastating epidemic—not to mention smallpox, diphtheria, and a world war—then there is hope for our generation. After all, history tends to repeat itself.