There was a time when coal fueled the very pulse of progress, powering industries, warming homes, and driving the relentless march of locomotives across the burgeoning West. Rich with black gold, coal mining carved deep into Washington’s identity, both literally and figuratively. Back then, the region echoed with the sounds of picks and shovels, its communities thriving on the deep veins beneath the earth until progress would ultimately render the industry obsolete. For Centralia, the dust would settle on the state’s very last coal mine for the last time in 2006, and its closing would mark a solemn farewell to a chapter of Washington’s industrial past that had smoldered for generations.

The First Flame: The Spark of Centralia’s Coal Mine

Coal reigned supreme in the nineteenth century in the Pacific Northwest, with outbound shipments of this vital resource being sent by the ton to power locomotives, heat homes, and fuel industries within San Francisco’s ports. Even before Centralia’s founding in 1886, coal was being mined there. However, the glow of this black gold faded steadily after World War I, leaving the industry a mere shadow of its former self by the 1960s.

Unfortunately for Washington, the decline coincided with a critical juncture for the state’s primary electricity source, hydropower, which had reached its absolute limit. Though all available hydroelectric sites had been exploited, the demand for electricity remained insatiable, and so electric companies turned to nuclear and coal combustion to keep the lights on.

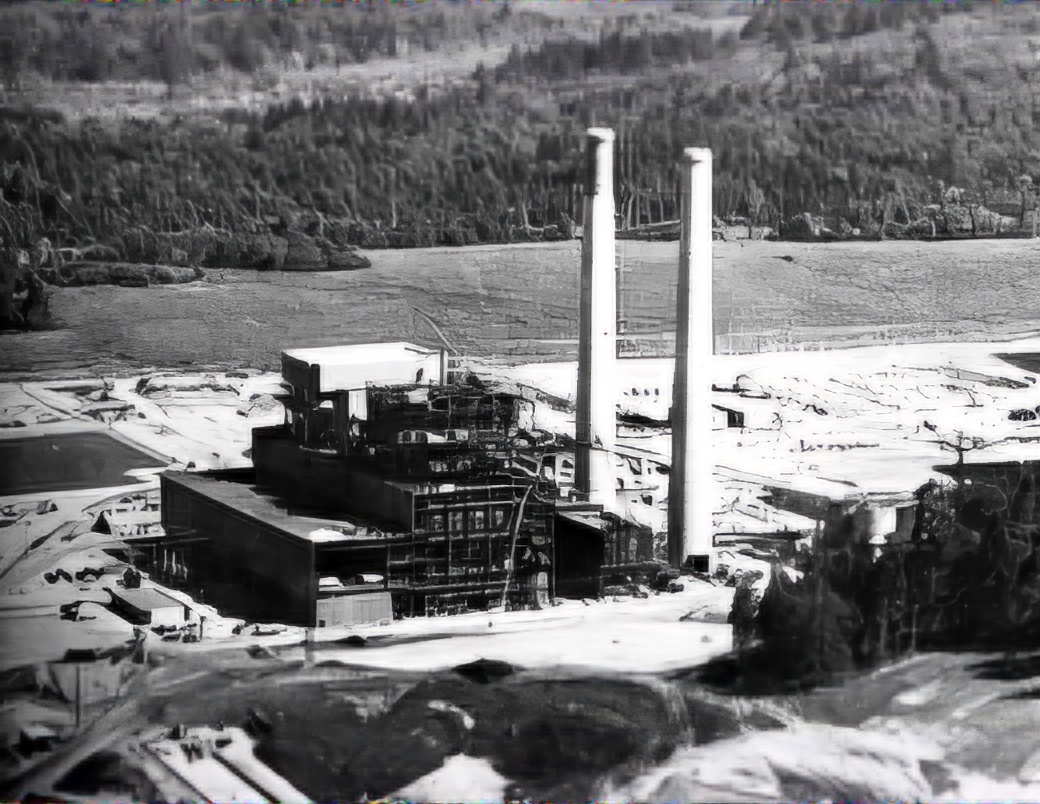

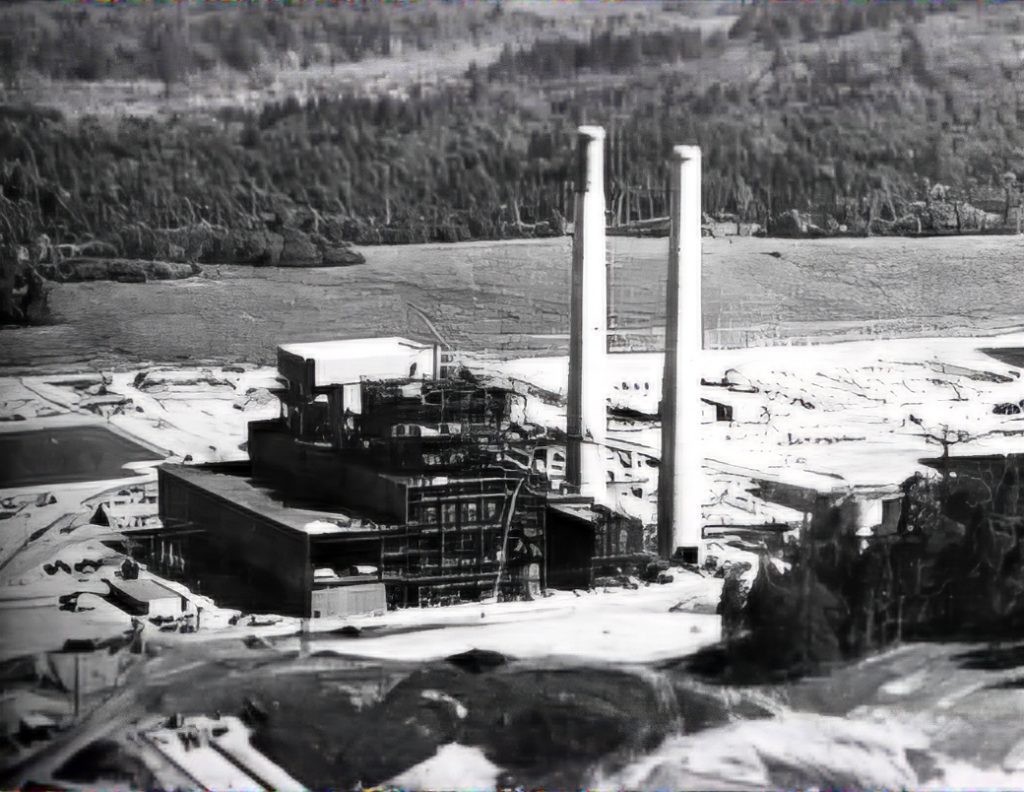

By the end of the decade, eight utility companies had joined forces to build a 1.2-megawatt steam-generation plant adjacent to a nearly 10,000-acre open-pit mine northeast of Centralia, making it the largest coal mine in Washington. Giant, construction-grade machinery tore into open pits to extract the coal, which was then washed on-site before being fed into the adjacent coal-fired Centralia Power Plant. It would become Lewis County’s second-largest employer, with the Centralia Coal Mine forever changing the region.

New Stewardship of the Centralia Coal Mine Under TransAlta

PacifCorp would operate the mine through the end of the 20th century, managing extraction across four open pits, the Upper and Lower Thompson, Big Dirty, Little Dirty, and Smith seams, all part of the Eocene Skookumchuck Formation. Even as the national coal market continued to crumble, the Centralia operation would continue to thrive for decades by serving its sister power plant exclusively, with coal hauling measured in continuous, high?speed cycles.

In May 2000, PacifCorp sold the coal mine to TransAlta Centralia Mining (TCM). The Canadian?based TransAlta Corporation purchased both the mine and power plant for $554 million, instantly elevating the complex to one of three flagship surface-coal operations under their global umbrella.

During the previous decade, PacifCorp had worked with environmental groups, state agencies, the National Park Service, and the U.S. Forest Service to develop a plan to drastically reduce emissions. Their solution was a scrubber system to reduce sulfur dioxide emissions from 65,000 to 10,000 tons per year. A key condition of the acquisition was the agreement that TransAlta would assume responsibility for implementing said solution and invest $200 million in emission-control upgrades to install the scrubber system.

End of an Era as the Centralia Mine Closes in 2006

Despite TransAlta’s substantial investment in environmental upgrades and its continued operation of the Centralia Coal Mine, an unavoidable economic reality began to emerge by 2006. The inherent impurities within the local coal meant that the escalating costs associated with its extraction and necessary washing processes simply became unsustainable. Financially, it was no longer viable to dig and clean the coal from Centralia when significantly cleaner and more affordable alternatives could be procured and transported from the Powder River Basin in Wyoming and Montana. This stark disparity forced the owners into a difficult, yet unavoidable, decision regarding the mine’s future.

The definitive end came on November 27, 2006, when TransAlta officially ceased operations at the Centralia Mine. As the last coal mine in Washington state, its closure carried significant weight, not just for the industry but for all of Lewis, as approximately 600 workers were laid off by what was the second largest employer in the county.

Adhering to federal regulations that require a 60-day notice for major layoffs, TransAlta decided to immediately halt all work within the mine to preempt potential accidents stemming from a workforce that was understandably distracted by the impending news. All employees were honorably kept on full pay and benefits for the entire 60-day period following the shutdown. Meanwhile, the adjacent power plant pivoted overnight to Powder River coal, and reclamation crews began filling pits, regrading, and the dredging of water sources while planting native trees and other natural flora.

Saying Good-bye in 2025 to the Centralia Power Plant

Even after the Centralia Coal Mine’s closure, the Centralia Power Plant remained Washington’s single largest polluter, with environmental groups also ramping up pressure for its closure. This was in large part due to concerns over climate change and regional air quality, including a haze in and around Mount Rainier National Park that had been blamed on the power plant. Annually, the plant contributed approximately 9.85 million metric tons of carbon dioxide between 2001 and 2009, equivalent to the emissions of over two million gas-powered cars.

This stark reality would propel legislative action toward its retirement. In 2011, Governor Christine Gregoire signed the TransAlta Energy Transition Bill into law, setting a definitive timeline for the plant’s permanent closure. This landmark legislation established a phased shutdown: one boiler unit retired in 2020, and the second unit is slated for permanent closure by the end of 2025. Throughout this process, TransAlta has demonstrated a commitment to supporting the affected community, investing $55 million in energy efficiency, economic and community development, and critical retraining initiatives for its workforce. This includes a $20 million fund specifically for education and retraining programs for employees impacted by the plant’s retirement.

The story of Centralia’s coal industry, a narrative etched deep into Washington’s industrial past, is rapidly drawing to its final close. From the roaring locomotives of the nineteenth century to the shuttering of its last mine in 2006, the region has continually adapted. Now, the focus shifts to the Centralia Power Plant itself, once the exclusive recipient of the mine’s “black gold,” as it prepares to follow its sister operation into history, marking a profound transition for the state’s energy landscape.