There’s something special in the rivers and trees surrounding La Wis Wis campground. Many visitors remark on it when they first go. You notice it from the minute you arrive – but what is it?

Some people say the presence is centered where the Ohanapecosh and Clear Fork rivers join. River confluences hold special spiritual significance, of course. They join rivers and give birth to new ones. La Wis Wis joins the Clear Fork and the Ohanapecosh, and from them is born the Clear Fork Cowlitz. The ancient people who frequented La Wis Wis are thought to have gathered at the confluence.

Northwest Sahaptin Texts contain narratives Native Americans shared with anthropologists. In them, Native American Jim Yoke says, “Coyote named all these places in this land …. There is a place there named Ohanapecosh … which stream empties into the Clear Fork above Lewis [Packwood]. On his route, Coyote came out of the water to the shore, and he said at this place, “People will dwell here.”

Forest Service archaeologist Kevin Flores confirms ancient people frequented La Wis Wis. “There are definitely archaeological sites all along the corridor up to Ohanapecosh,” he says. “They’re pre-contact.”

Long a special area for local Native Americans, La Wis Wis later developed importance for early settlers and visitors to the area.

With the discovery of Ohanapecosh Hot Springs in 1906, people around the country came seeking a mineral water cure for their ailments. “La Wis Wis was the stop-off point for people going to Ohanapecosh,” says Flores. First, people came by horses. Then in 1924 crews widened the trail into a Model-T road. Near the guard station, an old roadbed that was part of the road from Packwood to Ohanapecosh Hot Springs remains.

Forest Service workers say La Wis Wis is special. If Mt. Adams and Mt. St. Helens are the broad shoulders of the forest, and maybe Cispus Center is the brain, one could say La Wis Wis is the heart.

The founding of Gifford Pinchot National Forest occurred at La Wis Wis in 1949. A monument commemorating that event is near the picnic shelter, across the bridge spanning a small creek. Gifford Pinchot’s wife and son came to La Wis Wis for the founding ceremony.

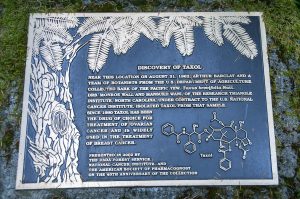

Scientists developing the important ovarian cancer drug Taxol came to La Wis Wis to collect bark samples from the Pacific Yew tree, which grows abundantly there. The scientists isolated Taxol from those samples. A monument describing the development lies near the picnic shelter, in the direction of the amphitheater.

Demand for Taxol once threatened the Pacific Yew with overharvesting, until synthetic Taxol came to market. Do not try do-it-yourself medicine by eating parts of the Pacific Yew. The tree is poisonous, especially its berries. It may not kill, but it will certainly havoc a person’s digestion.

Evolution of a Campground

The La Wis Wis Guard Station at the campground entrance embodies the Northwest rustic style developed by the Forest Service. The Civilian Conservation Corps built it in 1937 to house Forest Service personnel assisting travelers to Ohanapecosh. It appears on the National Register of Historic Places. The guard station had fallen into decrepitude over the years, but Forest Service workers, led by Rob Jeter, took up restoring the building on their own initiative. Collaborating with the White Pass Country Historical Museum and relying on Passport in Time volunteers, work started in 2012. They have nearly completed restoration. Passport in Time is a cultural heritage resources program sponsored by the US Forest Service, whose volunteers work to preserve the nation’s past all over the country.

The workers devoted themselves to preserving authenticity to the original design. “When you restore a building, you want to do it in-kind, is the term,” says Flores. For example, tongue and groove panels in the living room were labeled, taken down to remove paint, then carefully put back up in the same position. When they could not restore with original material, they faithfully reconstructed. For example, wood on the original exterior doors had so extensively rotted that restoration was impossible. Volunteers drew plans by reviewing drawings of the building and disassembling the old doors. Obtaining the same species of wood, they reconstructed the doors to identical dimensions as the originals.

Other daunting problems needed solving. At first, the team thought the chimney was pulling away from the building and might need rebuilding. Instead, they found the building was pulling away from the chimney. Fortunately, upon leveling the building, the two came back together.

The last planned Passport in Time session for volunteers to work on the La Wis Wis guard station occurred in spring 2019. Interested volunteers can look on the Passport in Time website for additional opportunities.

“La Wis Wis is truly a rare and unique building that likely wouldn’t be standing now if not for the PIT (Passport in Time) volunteers, Packwood Museum/Historical Society, and Rob Jeter,” says Flores.

La Wis Wis is 6.5 miles east from Packwood on US 12, the White Pass Scenic Byway. After leaving the highway, a one-half-mile road goes down to the campground. The guard station is left and the picnic shelter is right. Trailhead parking near the picnic shelter and at the Blue Hole trail in Loop H requires no day-use fee. Two short hiking trails, the Purcell Falls trail and the Blue Hole trail offer walking opportunities.

Please enjoy walking with the ancients and the pioneers in this special place.