This April marks the 160th anniversary of the start of the Civil War. Although Washington was a continent away from the bloody conflict and suffered no battles or destruction of property, the Civil War touched our fledgling territory in surprising ways. It ultimately helped to shape its future, including the future of Lewis County.

The Confederate attack on Fort Sumter began on April 12, 1861, but the news did not reach the Pacific Northwest for weeks. Word trickled slowly up the coast, first reaching Portland by steamer on April 28, then traveling north by land until the news was picked up and printed in Washington Territory newspapers in early May. Olympia’s Pioneer and Democrat ran the shocking headlines on May 3, 1861: “Attack on Fort Sumter!” “CIVIL WAR COMMENCED!”

It must have been terrifying for those early settlers living in the newly formed Washington Territory to hear about their nation at war. Doubtless, many of them still had family and friends back east who would be caught up in the bloody struggle that followed. Although Washington was not yet a state and had not even participated in the 1860 presidential election, most settlers loved their country and wanted to see the Union preserved.

Washington Men Answer the Call

That sense of loyalty prompted some of the territory’s men to head back east to volunteer in the Union Army. Washington’s first territorial governor, Isaac Stevens, was one of them. He accepted a commission as a U.S. Army colonel and was promoted to brigadier general by Lincoln. Stevens was later killed while leading his troops during the Battle of Chantilly in 1862.

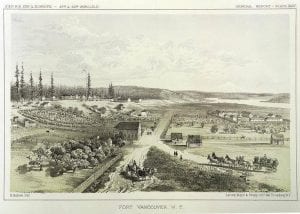

When the regular U.S. Army troops stationed at Washington forts were sent east to fight in the Civil War, others were recruited to take their place. The first Washington Territorial Volunteer Infantry was formed with around a thousand men from our territory. More were recruited from San Francisco. Manning posts throughout the Pacific Northwest, the regiment’s main task was to protect miners, settlers, emigrant parties and travelers in the Pacific Northwest territories.

The territorial regiment never fought a single Civil War battle. Still, they provided a valuable service to the settlers in our area and freed up the regular U.S. Army troops to fight for the Union back east.

Famous Civil War Generals Served in Washington Before the War

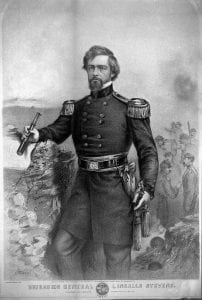

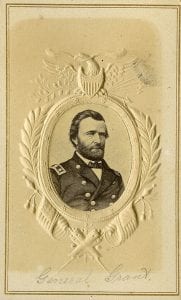

Some of the officers who later gained fame in the war, Ulysses S. Grant, Philip Sheridan, George McClellan, and George Pickett, all served with the U.S. Army in Washington Territory before becoming famous Civil War generals.

A few of these soon-to-be-famous generals met and dined with Lewis County residents on their military travels between Fort Steilacoom and Fort Vancouver. Grant, McClellan, and Sheridan were known to have been guests at John and Matilda Jackson’s home near Toledo. Grant also stopped at the Davis home in Claquato and at one time camped with his men under a large maple tree north of Centralia.

Grant, Sheridan and McClellan all went on to fight for the Union, but Pickett, who would later be remembered for his famous charge at Gettysburg, fought for the South.

Lewis County Residents Show Support for the Union

Despite the vast distance and slow communication from the war front, many Lewis County residents were fiercely loyal to the Union and showed their dedication to the cause.

In 1861, the Independence Day Celebration in Centralia was more than just a holiday in that first year of the war. It was a grand patriotic celebration. Two to three hundred residents flocked to Ford’s Prairie for the festivities. The Declaration of Independence was read, followed by an oration by the Honorable Judge McFadden. Judge Sidney S. Ford, the marshal of the day, then marched the crowd in a procession to a nearby bower where they feasted on a “bountiful repast.”

During the feast, thirteen toasts were given—an Independence Day tradition dating back to the end of the American Revolution. But that year, some of the toasts were far from traditional. Following several patriotic toasts made to the President of the United States, Governors of the States, the U.S. Army, U.S. Navy, the Union and the American flag, other toasts were made to “The Pacific Coast—may it never be a home of which Rebels can boast” and to “Sane minds, sound heads, and honest hearts—to keep the Union in all its parts.” The evening culminated in an Independence Day Ball at the nearby Halfway House.

In 1862, the women of Claquato gathered in the Harwood House to sew an American flag. Their masterpiece was an impressive 18-foot by 36-foot flag—the largest army regulation size at the time. It took 156 yards of material and cost $90. The flag was completed in time for the Independence Day celebration and proudly flown on July Fourth from a pole 120 feet tall.

Towards the end of the war, Claquato hosted a “Grand Sanitary Ball” to raise funds for the sanitation needs of Union soldiers. “Calls were made for food, clothing, needs, and other necessities,” remembered Annie Browning Royal, Lewis Davis’ granddaughter.

The festive dance was held in the empty Harwood House, and what a grand dance it was! Walls and stairs were removed, the walls covered with white muslin, greenery placed around the window frames, and kerosene lamps hung at intervals from wall brackets. Musicians played all night from a raised platform, and above it all hung the same enormous American flag suspended from the ceiling.

Folks danced all night under the Stars and Stripes. At a time when money was scarce, the $5-a-ticket ball was a smashing success, raising $225 for the Sanitary Fund. According to Arthur Denny, the patriotic ladies of Washington Territory “led every State and Territory in the Union, in sending supplies for the comfort of all the soldiers” in proportion to our population.

While the conflict was raging back east, daily life for the settlers in the newly-formed territory carried on much as it always had. Most were consumed with the daily struggle of tilling the land, caring for livestock, starting businesses and carving out a new life in the untamed wilderness.

However, when word came that the President was shot, the news touched them deeply. “One day as my grandmother, Angie Ford, was driving to Olympia with her father, they met a man on horseback who checked his furious speed long enough to shout, ‘Lincoln has been shot. He is dead.’ Judge Ford, staunch old Republican that he was, cried like a child and said he felt as though he had lost his own father,'” recorded Tove Hodge in Centralia, The First 50 Years.

How the Civil War Changed Washington

For most of the South and much of the North, the end of the war meant rebuilding the homes and lives devastated by the four-year conflict. But for Washington Territory, which had experienced neither battles nor destruction of property, the end of the war brought new life with railroads to help connect the people in the Northwest to the rest of the country, new towns that would spring up around the railroad, and a flood of new settlers that in a little over two decades would help increase our population enough to apply for statehood.

Before the war, Governor Isaac Stevens had been tasked with completing surveys for railroads into the newly-formed Washington territory. As a former U.S. Army engineer, Stevens completed his task efficiently, submitting his report to Congress in 1854. But the project stalled for a decade until the Civil War literally put it back on track. In 1864, Lincoln, believing a transcontinental railroad in the North was needed to help unify the nation, signed a charter for the Northern Pacific Railroad that would run from Minnesota to Puget Sound. Nearly 40 million acres in land grants were set aside for the project.

The Northern Pacific Railroad chose to build their first section of track right through Lewis County. This 105-mile section ran from Kalama to Tacoma and connected the Columbia River to Puget Sound. The Minnetonka, the first steam locomotive in the Pacific Northwest, began its service through Lewis County in 1873, a decade before the rest of the transcontinental railroad was completed.

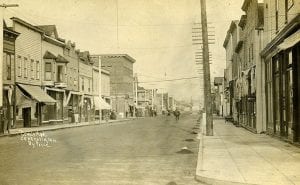

The coming of the railroad meant the birth and death of certain Lewis County towns and ultimately shaped the area’s development. For cities like Centralia, Chehalis, Napavine and Winlock, the railroad brought economic opportunity and growth. When early settler George Washington heard that the railroad would cross his land, he began dreaming of “building and caring for a little town, a striving center where neighbors would be dependent on one another.” Washington thoughtfully laid out a plat of the new town and named it Centerville because it was the halfway point on the railroad between Kalama and Tacoma. The town, later renamed Centralia, thrived as a railroad hub, just as Washington had envisioned.

In contrast, the residents of Chehalis had to fight for their stop on the railroad. When the Northern Pacific ignored several requests to build a depot in Chehalis instead of nearby Newaukum, the spunky and determined citizens resorted to building their own warehouse and waving down the train with red flags every time it came through. The railroad finally gave in, and a depot was constructed in Chehalis. This move gave residents the advantage needed to advocate for relocating the county seat to their town.

At the same time as Chehalis won their fight for the depot and new county seat, another little town lost. Claquato, the town that Lewis H. Davis had built to be the county seat and hub of Lewis County, faded into history when the railroad bypassed it.

New Settlers Flock to Washington After the War

The close of the Civil War brought an influx of new settlers to the Pacific Northwest. After the war, the U.S. government offered 160 acres to settlers who would reside for five years and make required land improvements. When ex-soldiers found out that their years of military service in the Union Army could be applied to the residence requirement, many flocked to Washington Territory to start a new life out west. Fifteen of those veterans were recipients of the Congressional Medal of Honor and are buried in Washington State.

Others took advantage of the preemption claims, which allowed them to purchase government land for only $1.25 an acre. The Northern Pacific Railroad also encouraged settlement in the area by selling off some of its land grants for less than $2.50 an acre.

Veterans and other folks who came in the years following the war settled in Washington towns, cultivated more Washington land, and joined with previous settlers in making Washington their home. Just over two decades later, our territory gained enough people to apply for statehood. In 1889, Washington became the 42nd state—finally joining the Union that many fought so valiantly to preserve.

Historical Note

When the Civil War broke out, Washington Territory aligned itself with the North. While there were definitely staunch abolitionists who advocated for freedom for all slaves, there were also pro-slavery Confederate sympathizers living in the same region who supported the South. However, the majority of settlers in Washington supported the North primarily because they wanted to see the Union preserved. Thankfully, the political and moral differences among the settlers here were less intense as back east and did not lead to bloodshed.